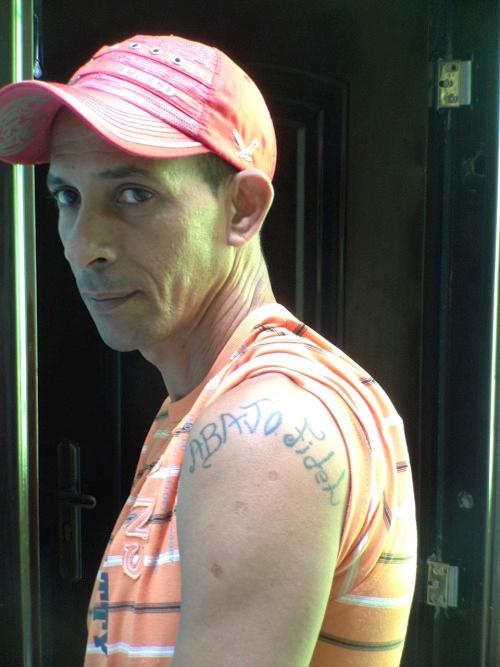

HAVANA — It’s just a few lines of blue ink, two words in a neat cursive. “Abajo Fidel” reads the tattoo on Roberto Hernandez Barrios’ left shoulder. But in one of Fidel Castro’s prisons — where Barrios just came from — those are fighting words. They mean, “Down with Fidel.”

Barrios’ right shoulder could bear a tattoo that reads, “Up with Obama,” for it was President Obama’s initiative to open diplomatic relations with Cuba that led to freedom for Barrios and scores of other political prisoners.

When Obama announced that deal in December 2014, most of the focus was on the headline prisoner exchange that started an era of new relations with Cuba. American Alan Gross, jailed for distributing satellite phones paid for by the U.S. government, was set free, and three Cuban spies in the U.S. were returned to Cuba, in what the administration insisted was not a swap. But a lesser-known group of prisoners was involved, 53 individuals who were supposed to be let out of Cuban jails later as a confidence-building measure.

Barrios, 48, was one of them. Some doubted whether Raúl Castro would comply, but on Jan. 8, Barrios was summoned out of his cell at Combinado del Este, Havana’s main prison. That morning, “I was surprised, I didn’t know anything,” Barrios recalls, and a colonel handed him a piece of paper saying he was free. Across Cuba’s archipelago of prisons, similar scenes played out dozens of times as “Obama’s prisoners” were released and sent home over several days in January. Here were men and women who had committed what the Cuban police state considers crimes: calling for elections, handing out fliers, writing anti-government slogans on walls or “failing to conform to the government” as demanded by Cuba’s revolutionary police state.

Roberto Hernandez Barrios was sentenced to five years for distributing copies of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (Photo: Patrick Symmes for Yahoo News)

Barrios’ crime may be the most spectacular of all — he was sentenced to five years in jail simply for distributing copies of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a U.N. charter that guarantees free speech, free association and political rights. Jail was “a horrible experience,” he said, “locked up with murderers, drug dealers and thieves. … It was a beautiful thing Obama did, for me, for Cuba.” But dig deeper into Barrios’ story, which I did during an hourlong interview at his modest Havana apartment, and you see why he never got an “Up with Obama” tattoo on the other shoulder.

Don’t compromise, he urges the American president. “I’m proud of Obama,” Barrios explains. “He’s part of the change here.” But any opening to the Castros will benefit “them, not the Cuban people.” He doesn’t feel free, even though he’s home again with his wife of 15 years, Niurka Fuentes, who he calls his “Lady of Iron” for standing by him during two years of jail. Although they are together again, he says, “We are still prisoners” of an authoritarian regime.

Asked what Obama should demand from the Castros, Barrios immediately replies, “The liberation of all political prisoners, and free elections,” two perfectly fair demands that would nonetheless torpedo negotiations with the Castros immediately.

“Oh,” Barrios adds, grinning in his dreamland, “and a boat full of cellphones.”

The 53 prisoners are the visible edge of Obama’s diplomacy in Cuba, but a cautionary one. Interviews with a handful of the ex-prisoners in Havana show that they are all grateful to Obama, personally, but they are consistently against his policies, the same ones that freed them. They argue that the U.S. should give no ground to Raúl Castro and that no opening to Cuba is worth compromising the value of human rights, elections or economic embargoes — not even to free prisoners like themselves. They want more isolation and confrontation with their enemy, not less. Call it a principled stand for human rights, or a contradiction of their own experience, but it is hard not to hear a familiar and tragic bitterness in their cries, the Cuban unwillingness to compromise.

Protesters in the Little Havana neighborhood of Miami hold a demonstration in December 2014 against President Barack Obama’s plan to normalize relations with Cuba. (Photo: Lynne Sladky/AP)

Hard-line rhetoric was long associated with an older generation of Cubans from Miami and Havana, who — on both sides — defined themselves by their support for or opposition to Fidel Castro’s revolution. A new era in U.S.-Cuba relations may be here, but the polarized politics are not going away. That demographic of anger may be fading in Miami, but in Havana, it seems to be refreshed almost constantly by a repressive system that has “a huge ability to produce prisons but not food,” according to Havana human rights activist Elizardo Sanchez.

While Obama’s opening has raised expectations among ordinary Cubans sky high, the Havana government has barely seemed to acknowledge that half a century of open hostility has ended. Economic reforms have created some movement in Cuba, but that sense of change seems absent in official propaganda. The familiar slogans of yesteryear are still present everywhere; although the spies known here as the “five heroes” are all back in Cuba, the streets are still full of painted slogans demanding their return. Raúl Castro spoke for only three minutes when he announced the restoration of diplomatic ties last December. Fidel Castro took months to acknowledge the changes, warning Cubans to beware of U.S. intentions.

The Obama initiative is working to open and reform Cuba, if only because the Castros have no alternatives to accepting it. Venezuela, the country’s current sugar daddy, is tottering, and the more pragmatic Raúl Castro is steadily pursuing economic reforms only as a backup plan. He is fundamentally opposed to the goals that are at the heart of Obama’s strategy in Cuba, namely using economic leverage to create a middle class and support independent professionals and civil society. From Havana’s perspective, that looks like a plan to destabilize and overthrow the entire system of controls put in place by the Cuban government. Sanchez notes that the three pillars of rule inside Cuba have always been repression, propaganda and strict economic controls, and the first two are still in place.

During eight months of secret negotiations with Havana, U.S. diplomats worked quietly to assemble a list of political prisoners to be freed in the deal. Sanchez was one of several people approached to confirm an identity, for example, or discuss a particular case, but he never knew that U.S. diplomats were working on something big. As a result of this secrecy, it was difficult to vet or even update the list, and it suffered from inaccuracies. Only 37 of the 53 prisoners were still in jail by the time Obama made his announcement on Dec. 17. That meant that Raúl Castro received credit for freeing 16 people who were, in fact, already free. Obama as well. His list of prisoners was a grab bag of recent, high-profile cases, most of them involving relatively short sentences, and to please the Cubans, it excluded eight people associated with violent attacks on the island. But the group of 50 to 60 political prisoners still in Cuban jails includes at least one person who has already served 25 years and who might have appreciated one of those extra 16 spots.

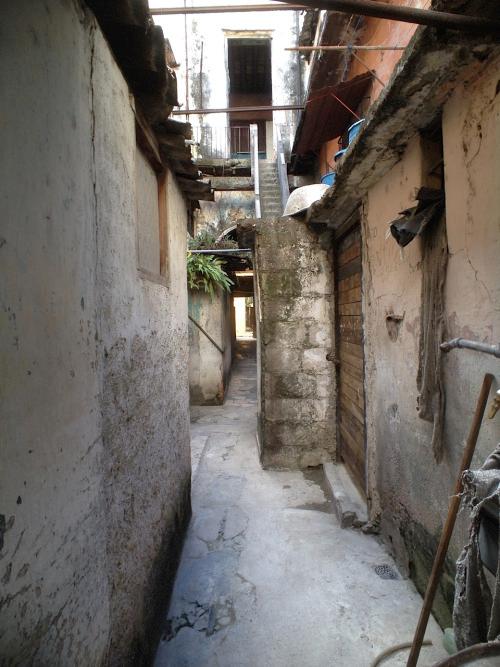

The group freed abruptly on Jan. 8 includes men like Willberto Parada, who by February was living in a tiny shed in a greasy, crowded, dystopian courtyard of Old Havana. “They let me out” of jail, he told me, “but under limits, thanks to the agreement between Obama and Raúl.” His neighbors who work for the block committee are required to report on him. “They listen to everything,” he said, of people living just feet away, behind improvised walls separating the courtyard into cuarteria, or microapartments. “Cubans have no privacy.”

The courtyard near Willberto Parada’s residence in Old Havana (Photo: Patrick Symmes for Yahoo News)

In March 2013, Parada recounted, he had tried to demonstrate against the government on nearby Obispo Street, the heart of Havana’s tourism district. The first time, he was verbally abused and threatened by police and government sympathizers; the second time, he was beaten, arrested and given four years in jail. He was in the Valle Grande prison on Jan. 8, when, “fantastically,” they “took me out of my cell and gave me a piece of paper saying I was free.”

“My respect for President Obama, he’s a great man,” Parada says, “but he shouldn’t trust Raúl after 53 years. Any changes should benefit the public, not [the Castros].” Parada’s caution was hard-won, and sincere: He expects to continue denouncing the government and was already picked up by the police once since coming home.

On the other side of Havana, many miles from any tourist zone, I found similar sentiments from Haydée Gallardo Salazar, also freed on Jan. 8. She joined a political party called the Movement for a New Republic. Officers of State Security arrested the party’s leader, and as allowed by Cuban law, she went to inquire about him at a public office called Section 21. Instead of information, however, she says she was offered a deal: Work for State Security as a spy. She told them no, after which she says she was berated, called a mercenary and then struck hard on her shoulder. She was then placed under “preventive detention” and taken to a women’s prison. Eventually she was sentenced to two years and six months. The official charge was causing public disorder at Section 21, but, she says, “My supposed crime was to be … a member of the opposition.”

She lost 41 pounds in jail. Getting out of jail hasn’t provided any easy resolutions. “It is one month and three days since my liberation,” she said, in a two-room apartment she shares with her husband, Angel Figueredo Castellón, and framed pictures of cats. Sitting under a Cuban flag, beside a collection of books on freedom and democracy, she says, “I’m still stressed and under a lot of pressure.” The man she called “Oh-ba-MA” had “acted from the heart” in freeing prisoners. But she was “very irritated” with him too. “The only one who will benefit from this opening are the Castros.” Economic improvements will simply fund more government repression. “I don’t agree that they should lift the embargo and make more millionaires.” She made a pyramid in the air with her hands, to represent power in Cuba. “The ones up here are the Castros,” she said. No one else would benefit.

This reaction to Obama’s opening has shattered long-standing friendships in the Cuban opposition. The once-moderate blogger Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo has denounced Obama as every dictator’s best friend, while Yoani Sánchez, author of the influential Generation Y blog, has supported the changes. The island’s most visible opposition group, the Ladies in White, recently expelled a founding member for her support of the Obama plan. Re-enacting the worst aspects of Castro repression, a crowd of enraged civil rights activists in white stormed the offender’s house, chanting and denouncing her, and then literally tarred her.

U.S. policy is predicated on the idea that economic openings, access to information and the rise of a middle class will undermine the Castro system. Gallardo Salazar offered a prayer to “God and Santa Rita” that conditions improve on the island, but said, “We can’t just think about Cubans lacking food and shoes and so on. That’s necessary, but society has to feel secure.”

The Castros were stalling, she suggested, always coming up with another excuse for a fight — little Elián Gonzalez or the repatriation of the five Cuban spies. Now it was indemnity payments for damages dating back decades, or the return of Guantanamo Bay. They blamed the U.S. for everything. “It was the Castros who made Cubans afraid,” she countered. The problem “is internal. Who bans free expression? The Castros. If we had free elections and many political parties, then the Castros wouldn’t be a threat.”

Her wish list for Cuba: “Milk for babies. Food for Cubans. End the repression. The end of the Castros.”

That’s a terse and deceptively simple list. Milk for babies is still rare in today’s Havana, and the only question is how to make more of it: engagement or isolation? Obama simply decided to stop doing the thing that failed year after year, and start doing something else. As the fates of the released prisoners show, that policy is already bearing fruit, however bitter.

Source: Liberated Cuban prisoners to Obama: No more deals like the one that freed us!