Syria is an enthusiastic state sponsor of terrorism and a fiendish fan of torture and oppression. But have you tried the stuffed grape leaves? PATRICK SYMMES invades before the coalition of the willing can.

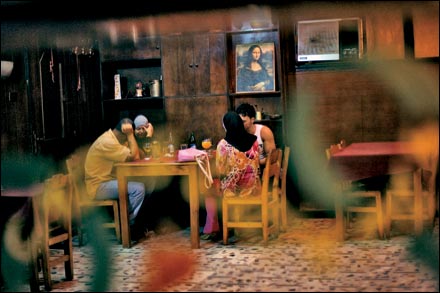

Photo: Seamus Murphy

Photo: Seamus Murphy

Photo: Seamus Murphy

Photo: Seamus Murphy

Photo: Seamus Murphy

I DON’T MEAN TO PICK A FIGHT HERE, BUT ARABS ARE LOUSY DRIVERS.

It’s not a religious thing: Sunnis, Shiites, Maronite Catholics, Greek and Syrian Orthodox, the Druze and the Alawites—they’re all equally bad. I actually met a guy in Beirut who owned a driving school. I laughed so hard beer came out my nose.

When my taxi first exploded from Lebanon into Syria, I wasn’t laughing anymore. On the Lebanese side of the border I’d grabbed a mandatory-yellow Plymouth Gran Fury, an early-1970s behemoth with tassels hanging from every surface. The backseat was covered in shag and big enough for a dance party. The dash was equipped with a miniature fan, a verse from the Koran, and a framed picture of Syrian president-for-life Bashar al-Assad. The hood ornament had been pirated from a Cadillac El Dorado. Pimp my ride, Baathist edition.

I’d been counting on clearing customs with a tourist visa and a smile, but the camouflage-clad Syrian border guard wasn’t buying. When he noticed the unusually large camera beside me on the seat—it more or less screamed “journalist”—he started yelling. I chuckled. He pointed an accusing finger. I made smiley faces. He thundered. But meanwhile the queue of cars behind us was growing, and in loud revolt. Harassed by the dunning of a dozen air horns and goaded by indignant drivers, the guard abruptly waved us through. The Gran Fury rocketed toward Damascus, one in a clot of cabs and cars unleashed all at once.

A true muscle car, the Fury had every advantage on a wide-open, curving expressway. We easily overtook a 1950s Nash Rambler, swerved around an overloaded minivan, and nipped past a Dodge Dart. As we topped 75 miles an hour, a titanium-silver fuel-injected 2005 Mercedes breezed past. Undaunted, my driver gunned it to 87. I was watching the speedometer because the Fury’s seat belts had gone the way of the original eight-track.

Fifteen minutes, total, and Damascus came into sight. That was all it took to see the enemy capital in the distance. Fifteen minutes and you were further into the mystery of Syria than the United Nations was at the time. The UN is investigating Syrian officials for their widely assumed complicity in the assassination of Rafik Hariri, the former prime minister of neighboring Lebanon, in a Beirut car bombing last February. Just 15 minutes and you were closer than Saint Paul was when he was knocked off his horse. Fifteen minutes and you were as close as Muhammad supposedly ever came. Arriving with his armies in a.d. 630, he compared the first sight of Damascus to a glimpse of paradise, but he only saw the city from afar, at night, and never entered its gates.

Another 15 minutes across a dust bowl and we roared into the city and screeched into the central taxi yard so hot you’d think an Israeli tank column was on our tail.

IN AUTOMOBILES AND OTHER WAYS, Damascus, like Havana, can look like the city the world forgot. It is arguably the oldest living settlement in the world, inhabited for almost 10,000 years, yet now best known as a capital of tyranny, headquarters of a military regime isolated by international opprobrium and feared by its own people. Syria is your friendly neighborhood thug, its government a milder variant of the same Baath Party (secular, socialist, and sadistic) that held Saddam’s Iraq in its grip. With the latter regime deposed, Syria has taken over the role of rogue state: accused of “support for terrorism,” “false statements,” and “interference in the affairs of its neighbors” (Condoleezza Rice); “helper and enabler” of terrorists (George W. Bush); “one of the major supporters of terrorism” (the Pentagon).

Axis of evil, junior division. But if Syria’s government has been cast as the black hat in international affairs, the Syrians themselves make the sweetest of villains. The population of 18 million is about 70 percent Sunni Muslim but is controlled by the Alawites, a small Shiite offshoot—comprising roughly 12 percent of Syrians, including the Assad family—that deifies Muhammad’s son-in-law Ali. Fearful of the Sunni majority, the Alawites keep a lock on military and security posts, and defend their secular regime tooth and nail: When dictator Hafez al-Assad died in 2000, after a nearly 30-year rule of defeat and stagnation, the constitution was literally rewritten overnight to elevate his 34-year-old son Bashar. Things began to look up when Assad the younger, an ophthalmologist trained in England, took over. Cell phones were made legal, then satellite dishes, which now crowd the skyline of the capital, challenging the monopoly on information. Tourism has grown 5 percent a year, with Europeans and even American Christians drawn to a breathtaking stockpile of Greco-Roman–Byzantine–Crusader ruins, religious shrines, and social graces drawn from the golden age of Islamic civilization.

But the pleasures of Syria (uncountable historical treasures, sympathetic people, sublime food) come with drawbacks (blistering deserts, Mad Max roads, a murderous police state). Bashar’s sham election earned him 92.79 percent of the vote, security forces killed at least two dozen Kurdish demonstrators in March 2004, and you can still find the leader of the 1985 Achille Lauro cruise-ship hijacking in the Damascus phone book. A year ago, the Syrian government dramatically enhanced its reputation for stupidity by allegedly sponsoring the assassination of Hariri, one of its sharpest critics. The massive car bomb that killed the former prime minister backfired: Street protests erupted throughout Lebanon, Muslims and Christians marching together in what became known as the Cedar Revolution. By last April the demonstrations had forced out the 20,000 Syrian troops that had occupied Lebanon since 1976. Humiliated, the last Baathist army of conquest retreated to Damascus.

Confused, defensive, under investigation, the Syrian government began to look shaky. Days before my arrival last fall, The New York Times advised that the “veneer of normalcy” could crack at any moment. Most fatefully for its future, Syria has become a kind of small-scale Cambodia to Iraq’s Vietnam, a transit route and sanctuary for the insurgency next door. The foreign jihadis who slip over the 376-mile border are only a tiny minority in Iraq, but they have drawn Washington’s wrath onto Damascus. In October, a White House meeting mapped a range of options for punishing Syria. Increased economic sanctions. Delta Force missions. Or simply the continued initiative to keep Bashar off balance—”rattling the cage.” In November, The Washington Post reported that Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had ordered CentCom, the U.S. Central Command, to prepare a “strategic concept” for Syria, the precursor to a war plan.

Only the smart bombs know the coordinates of the future. The one sure thing is that, squeezed between Iraq and a hard place, Syria is in for a bumpy ride. Like Cuba in 1957, this twilight shall not come again. And so, to the tune of the saber rattling, I went to sing the praises of the enemy one last time.

EVERYTHING IN DAMASCUS is fabulously, incomprehensibly filthy, coated in talcum-fine desert grit. It is a city of more than a million, with an outermost layer of cement plants and car dealerships, the dry skin shed by a snake. Inside that husk is a noir new city, a wilderness of empty architectural gestures, never-finished towers of rebar, and abstract avenues that lead to theoretical traffic circles. Orwell designed this Damascus: The Ministry of Information prevents anyone from having information, the Ministry of Economy and Trade strangles the economy, and the Ministry of the Interior meddles in other country’s affairs. Every car, shop, and house carries a painting, photo, or decal of President al-Assad—Hafez or Bashar, take your pick.

At dusk, this new city drops its shutters, leaving scattered pockets of seedy nightlife—vinyl “superclubs” that open at midnight, stocked with expensive liquor and Ukrainian dancers. But in the mornings, a better Damascus emerges, the Old City. Still girded with an oval of Roman walls pierced with nine gates, this ancient Damascus is packed with sweet shops, antique dealers, minarets, and, at its heart, the eighth-century Umayyad Mosque, where the relics of many religions slumber side by side.

On my first morning in town, the mosque was crowded with busloads of Shiites from Iran and Iraq. The black-clad women and weeping men moaned and beat themselves at the shrine of their great martyr, Hussein, whose death 1,300 years ago begat the long, passionate drama that is Shiism. But the mosque offered dreams for the faithful of all stripes: Greek lettering on the foundation stones, from when it was a Christian cathedral; the remains of a third-century Roman temple; and, in the main prayer hall, a marble-clad catafalque said to contain the head of John the Baptist, who was executed by Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee, around a.d. 30. Some Shiites got the wrong idea and fell to their knees, mistakenly crying out, “Hussein! Hussein!”

You can’t throw an egg in the Old City without hitting a monotheist. In the Christian quarter, I ran into a group of 36 Spanish Catholics walking in the footsteps of Saint Paul. Paul had been blinded (and unhorsed) outside the city by a “light from heaven,” and the Spaniards were now taking literally the injunction he’d received in Acts 9:11, to “arise and go into the street called Straight.” Today the Via Recta has finned Cadillacs on it, but you can still see the Roman arch Paul would have passed under. The pilgrims had just come from the Old City wall where, wanted by the authorities, the fugitive evangelist had escaped in a basket lowered on ropes.

“It’s a revelation to finally know what they knew,” Juan Botey, a quiet, lean, gray-haired Catalan from Barcelona, explained. “To see the places they stood.”

The Spaniards were almost silent as we marched down to the arched basement where Paul had been cured—well, more or less the place, since the location of these spots changes every few centuries. Like the Shiites, though, the Catholics had enough wonder to overcome navigational difficulties, and they launched into a mass in their soft Catalan dialect, not too far from the Latin that Paul would have heard in his day.

On the way back through the Muslim quarter, lost in a maze of alleys, I passed a few coffee shops stocked with European hipsters smoking hubble-bubble pipes and stumbled onto a converted old mansion, the headquarters of the Syrian Environmental Association (SEA). They were holding an open house, showing off art projects made from recycled materials and handing out “Don’t Mess with Damascus” brochures. The chairwoman, a former director of Kalamoun University named Dr. Warka Barmada, quickly admitted that there isn’t much of an environmental movement in Syria. She pointed to the Barada River, once a mountain stream sparkling through Damascus. If Paul were baptized there today, he’d come up with a plastic bag on his head and a bad rash: The Barada is a putrid trickle down a garbage-laced culvert.

Beyond the city, problems are legion. Logging in the northwest hill country. Desertification. Uncontrolled pollution by unaccountable industries. (But few petroleum spills—sadly for Syria’s sputtering economy, this is one Middle East sand trap with little oil.) President al-Assad has set up a few tiny nature reserves, and a population of endangered oryx has been restored in the desert; other than that, Barmada said, little has been done “that I’m aware of.”

“I’m not talking politics,” she quickly cautioned. Syrians can only talk about what she called “politics with a small p,” meaning issues of daily competence, the performance of government services. “We want to change from within,” she added, “not by opposition.”

But environmentalism can’t help but carry a whiff of the capital P. The SEA, Friends of Damascus, and two other green groups are some of the only nongovernmental organizations in Syria. Aside from the dismal national soccer team, just about the only thing it is legal to complain about is the environment. Where else can young idealists go, if not to Dr. Barmada?

Syrians are largely indifferent to things like pollution, she said. “Since we have been a socialist country for a long time, people got used to saying the state will take care of every problem.” But attitudes were changing, she pointed out, “now that we are going through a transition.” She meant the vague changes Bashar had promised: economic reforms, the arrival of the Internet, even free speech. Little of it has come true.

Transition is a Syrian euphemism. A transition to something unspecified, a world after. After Bashar? After a cruise-missile strike? A civil war? The country was a cipher to its own people. Meanwhile, the Baath elite partied in the thumping nightclubs of Bab Touma, just inside the Roman wall. No-neck men in black suits and T-shirts manned the doors there, whisking in lanky honeys in tight jeans. I spent an hour one night spying from a rooftop restaurant as military officers caroused in the beer garden below. While demolishing ranks of stuffed grape leaves, grilled peppers, and 2004 Lebanese petit verdot, I learned three things. First, the enemy has terrible taste in music. Second, Syrians probably invented food. And third, Muhammad had a point: At night, under a cold moon, all the grit disappears, and the hillsides glitter with amber lights. Heaven, even here.

CLASHES ON THE IRAQ BORDER, foreign jihadis trickling eastward, U.S. Special Forces allegedly conducting covert incursions inside Syria itself: It seemed like a fine time for a road trip.

I had a guide in mind. In 1909, before he was “of Arabia” and when Syria was still part of the Ottoman Empire, 21-year-old T.E. Lawrence had set out in similar circumstances—instability, banditry, and halting Arabic—to write his Oxford thesis on the Crusader castles scattered along Syria’s coast. For two months he mapped the dozens of visually linked keeps and signal towers built by the European invaders in the 11th and 12th centuries, sleeping in Arab houses and walking huge swaths of the Nusayriyah Mountains with a sketchbook, a pistol, and a Boy Scout shirt tailored by his mother with extra pockets. Except for the pistol and shirt, I was good to go.

Reaching the first and greatest of these castles, Krak des Chevaliers, was a three-hour drive on good roads and the edge of death. I’d quickly learned to pick older, feebler taxis, but the rounded Renault was still squeezed from both sides by trucks going 70 as grinning motorcyclists and panicked donkeys wove crosswise through the mix. Occasional interlopers shot at us headlong, down the wrong side of the divided highway. The bleak landscape was interrupted only by giant statues of the late dictator, Hafez al-Assad, and a road sign that read thank you for visiting hama. Hama is where dear old Hafez used tanks to kill at least 10,000 of his citizens while crushing a 1982 rebellion.

Tucked up inside a pass, controlling the high ground, was Krak des Chevaliers, Castle of the Knights, a staggering work of medieval ambition with exquisitely preserved double-curtain walls, towers, battlements, and, yes, a spot for dumping boiling oil on the enemy. Lawrence said it was better than any castle in Europe. From the top of a tower once occupied by Richard the Lionheart, I could see, a dozen miles to the northwest, a small fortress clearly visible against the sky, the next link in the Christian war machine that held much of this coast for close to two centuries.

The Lawrence trail led me to the quiet seaside town of Tartus, where sidewalk cafés gave off clouds of sweet apple tobacco under a full moon. The Crusader fort here had a good restaurant inside the walls. The next day I ran north in a rusted Mercedes 300D. The big Crusader fortress at Marqab, made of black basalt, loomed over the narrow coastal plain like a thundercloud, but the coast itself, a lost bit of Mediterranean Riviera that Lawrence had loved, was now a trash-strewn eyesore, decorated with absurdly huge cement plants and terminals for Syria’s tiny oil industry. Even on the isle of Arwad, where a small castle marked the Europeans’ last foothold in the East, nobody had gotten Dr. Barmada’s memo. Scrap metal and oil slicks ruined the crashing of deep-blue waves.

Lawrence led me on. In Latakia, the country’s main port, neon lit up the busiest nightlife north of Beirut. Home to the fiercely secular Alawite leadership, Latakia was the least conservative place in Syria, a small city with as many bars and restaurants as Damascus. The hotels were taken up with spectacular weddings, floral atrocities conducted to blaring pop music and live video feeds. Alcohol was everywhere, women went around in short skirts, and just once, at the beach the next day, I saw that rarest of all things, the Arab bikini.

Above the city, the last green juniper forests of Syria concealed another incomprehensible, absurdly grand castle, Qalat Saladin. My cheery Latakian driver screeched his Lada right to the edge of an overhang to show me why: Ringing a tiny mountaintop, the fortress was surrounded by steep ravines on three sides. The Crusaders had hewed out the rock on the fourth side to make an unassailable edifice. But in 1188, they’d been blasted out in just two days by the great Islamic general Saladin.

While standing there, imagining the giant catapults that had shattered the walls, I was nosed off the road by a minivan that disgorged 15 Dutch tourists. We glared at each other. Syria is like Turkey in the sixties: People expect to have a ruin all to themselves, thank you.

Their local guide broke into a grin when he learned where I was from.

“You see?” he said, turning to his Dutch clients. “There is no terrorism in Syria. Even the American is alive.”

“IT WAS FIVE O’CLOCK on a winter’s morning in Syria. Alongside the platform at Aleppo stood the train . . .” It isn’t often remembered how Agatha Christie’s most famous book begins, but it was Syria that put the “Orient” in Murder on the Orient Express, and Aleppo, the great highland city of the north, where her sleuth, Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, waited for his train. Christie was writing what she knew: Married to an archaeologist, she spent much of the 1930s living in a mud-brick house at a remote dig site outside Aleppo, typing furiously.

The UN had just sent its own Hercule Poirot into Syria to solve a case, namely, the assassination of Rafik Hariri in Beirut. The detective this time was Detlev Mehlis, a former prosecutor from Germany who, like Poirot on the Orient Express, had to sort through a rapidly expanding array of evidence that pointed him to the inescapable conclusion that, just like on the Orient Express, not only had almost everyone been involved but almost everyone was going to get away with it.

Who were the six men who shadowed the prime minister’s convoy in Beirut? (They flew away 90 minutes after the bombing.) Who bought the six cell phones they used? (A Lebanese from a pro-Syria party.) Who drove the white Mitsubishi van into Lebanon? (A Syrian colonel.) Where was the van stored before being loaded with more than 2,200 pounds of TNT? (At a Syrian military base.) Which Syrian officials were present at the meeting last February where the crime was green-lighted? (The president’s brother Maher and his brother-in-law, Asef Shawkat.)

For his own protection, Mehlis was stashed in a “secret location” outside Damascus—a red-roofed hospitality complex in the first range of hills, clearly visible from any Gran Fury crossing the border. Not long after he left, one of the suspects he’d interrogated, Interior Minister Ghazi Kanaan, blew his own brains out. (Or was it murder?) Now the case had everything, even a smoking gun.

Like Poirot, I greeted the dawn on a train platform in Aleppo, having made the early run up from Latakia. The train was less Orient Express than early Brezhnev, and the Aleppo station had been improved with murals of Baathist astronauts and victorious Syrian armies. Despite the murals, Aleppo has changed at a glacial pace over the past 6,000 years. Recent big events have included a sacking by the Tartars, in 1260. They pulled down the glorious 11th-century hammam—marauders disdain bathing—but it was rebuilt, and a scalding trip through the steam room, a vicious pummeling, and a cold orange soda set me back $5.

I wandered Aleppo’s enormous Armenian quarter, packed with ancient churches and vendors of delicate sweets. (They also have the head of John the Baptist’s father, in case you didn’t get your fill in Damascus.) There were miraculous and medieval sights around every corner—soccer-playing imams in one place and, down the next alley, cheery children hammering metal inside a Dickensian workshop. Like any police state, Syria has little crime, so the only danger I faced in the souk, the huge covered marketplace, was being run down by a donkey messenger. Crumbling but alive, too poor to be ruined by progress, decorated with old cars and European tourists, Aleppo is a desert flower that persists only in the adverse conditions of geopolitical hostility and a moribund dictatorship.

In the 1950s and ’60s, a misguided attempt at modernization bulldozed some wide avenues through these old neighborhoods to make way for a few featureless plazas and office towers. Only a nitpicker of satanic proportions would obsess on how these few alterations had ruined the city, but there was such a man: Mohammed Atta, the ringleader of the September 11 attacks. A student of urban planning in Hamburg, Atta had come to Aleppo to write his college thesis. The young Egyptian loathed the way that a Le Corbusier grid had been superimposed on the crazed streets of Aleppo, which he viewed as a pure and organic expression of Islamic social relations. He left in 1994, nurturing a seed of hatred for Western architecture.

I poured gin and tonic on Atta’s soul in the bar at Baron’s Hotel, a symbol of everything he hated—grandly European, frankly colonial, a faded headquarters for Western cultural subversion. Christie lodged here in the 1930s; on the wall was a bill from April 1, 1914, made out to “Monsieur Laurence”:

4 jour pension 32 piastres

menu a repas 3 piastres

limonato 2 piastres

T.E. had walked much of the distance I’d just covered, arriving in Aleppo to discover himself reported dead in a local newspaper. He got over it: “Aleppo is all compact of colour, and sense of line,” he wrote in a letter home. “You inhale Orient in lungloads, and glut your appetite with silks and dyed fantasies of clothes.” The days were easy to fill as he had, roaming widely in the surrounding hills, consuming an endless buffet of ruins, civilizations piled atop one another. At the Dead Cities, a whole archipelago of old Roman towns, I met shepherd boys with the names of Christian emperors, and a Dutch archaeologist in a thrilled state of despair. Like Lawrence, like Atta, she was here for her thesis, trying to do six months of research on a one-month visa. Snooping where I shouldn’t have, in fading light, I slipped and slid into a dank tomb. It was filled with cobwebs, a broken sarcophagus, and 1,500-year-old bones.

I shot out of that hole so fast, the shepherds were still laughing ten minutes later.

LAWRENCE LEFT SYRIA A STUDENT and returned a conqueror, at the head of the Arab Revolt in World War I. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Syria and Lebanon became French mandates, and since both attained independence in the 1940s, the two countries have been entangled in a bitter dance, partners in a bad marriage, each defined by the other. Syria has the plains, Lebanon the mountains; Syria the quiet uniformity of a terrorized population, Lebanon the raucous politics of balkanized factions ready to slit one another’s throats. Syria, with its impoverished millions, has the big battalions; little Lebanon, with just under four million people, has the capitalism, the ski resorts, the wine, and the forests. Whatever happens to Damascus will also, most likely, happen to Beirut. So I took a detour.

The man who did the most to instigate the still unfolding divorce between Syria and Lebanon was Walid Jumblatt, clan chieftain and warlord of the Druze, an esoteric Islamic sect scattered through Syria, Israel, and especially southern Lebanon. I found the warlord at sunset in his fortified château in the Druze stronghold of Moukhtara, in the high, stony Shouf Mountains, an hour from the Syrian border. Druze guards with pistols frisked me with practiced ease as Jumblatt waited, talking on his cell phone. In his late fifties, he wore faded jeans and a collar-length fringe of long ringlets that tumbled down from his chrome dome. Surely he is the only warlord in the world who dresses like Frank Zappa, parties with Joe Cocker, and looks like Mr. Magoo.

The Druze were perhaps the only political winners in Lebanon’s 15-year civil war. Just to review, Christians and Muslims slaughtered each other (1975), the Syrians invaded with 40,000 men (’76), the Sunnis and Shiites fought each other (throughout), the Israelis invaded (’78), there was a depraved free-for-all (’79–’81), followed by a Beirut bombing of U.S. Marines (’83), the return of the Israelis (’84), and daily-shifting alliances and all-out wars between the Druze, Shiites, and Sunnis, with endless rounds of backstabbing among the Palestinians, Christians, Druze, French, and Americans. The two things to remember are that everybody ran out of ammunition in 1990, and that 1975 is now the name of a chic Beirut nightclub with fake bullet holes and sandbags for chairs.

Since the friend of my enemy’s enemy is the enemy of my friend’s friend, Jumblatt combined the battlefield prowess of the Druze with a fleet sense for when to abandon an alliance. A longtime ally of the Syrians, he’d been the loudest in calling for their ouster, even before the Hariri assassination, and had ridden the 2005 Cedar Revolution to a position as one of the most powerful men in Parliament.

Jumblatt led me inside to sofas in his vaulted office, where we were joined by his five-month-old puppy, a shar-pei named Oscar who gnawed on a coffee table. Following a time-honored Druze doctrine of takia, or protective dissimulation, my host pretended he didn’t know who killed Prime Minister Hariri.

“Except rumors, I have no idea,” he said, not bothering to conceal a wry smile. “In Lebanon you can hear all kinds of gossip. Lebanese people know everything.” He did blame the Syrian government for decades of crude political manipulation. The crimes were ongoing: Since Hariri’s death, a dozen Lebanese critics of Syria had been dispatched, one by one, with blocks of plastic explosives. The latest attack had occurred just two nights earlier: Not long after a popular journalist had attacked Syria on television, she turned the key on her Land Rover and it blew up.

Jumblatt’s office was a temple to warlord kitsch. A onetime client of the Soviets, he had a fabulous collection of their dress uniforms and vast canvases depicting the Red Army, along with velvet cases of Soviet, Lebanese, and Ottoman military insignia and medals. Since his father and grandfather were both assassinated, Jumblatt also kept a rack of six beautiful sniper rifles—and an artillery-spotting scope aimed over the valley below. When he stepped out to take a call, I inspected the vertical file folders on his desk. They were stuffed with pistols. Five semiautomatics, each sitting on a stack of five clips.

As the firepower hinted, Jumblatt was pessimistic. “The new Lebanon will be like the old Lebanon,” he warned. “Same old troubles. We will see. It depends on American policy.” He feared that the “neocon disaster” in Iraq would spill over into Syria. Any collapse would affect vulnerable, poorly balanced Lebanon.

Jumblatt led me back outside, past a huge marble sarcophagus. “Roman,” he said. “I got this in the time of looting, the eighties. I paid $10,000. Very cheap.” During the civil war, when half the antiquities in Lebanon were being sold abroad, Jumblatt had bought a priceless array of mosaics, which were now on display at an Ottoman palace across the valley. Joe Cocker played a good show there a few years ago, the warlord noted with satisfaction.

As we said goodbye, Jumblatt urged me not to miss Lebanon’s famous cedar forests. King Solomon’s temple was made from these strong, fragrant trees. There were only two stands of the old-growth giants left, one right here in the al-Shouf Cedar Nature Reserve.

Like his father, Jumblatt had ordered the Druze to plant cedars, three million young trees now growing inside special reserves up and down the mountain range. Although the cedars grow slowly, they can drive their roots down through the cracks in solid rock. Any man who plants three million trees can’t be a total pessimist.

THE NEXT MORNING, a Druze park ranger named Hassam Ghanim took me up to 6,500 feet, and we entered the al-Shouf reserve. Ghanim led me to an impressively gnarled cedar, black with age, with two trunks rising in a V. “One thousand eight hundred years,” he said, “if you like and you love.”

I liked and I loved. The tree was my size when Muhammad preached, the height of a house when Byzantium fell and the Ottomans arrived. It had ridden out the civil war because the Shouf Mountains were a no-go zone, the scene of brutal massacres. Wild boar, porcupines, foxes, even wolves had endured here for the same reason.

Ghanim claimed, doubtfully, that this was the “oldmost tree” in Lebanon, but there was a rival stand of cedars in the north, and I wandered that way, hoping to find some enduring lesson in the old giants’ survival. This meant heading up the Bekaa Valley, whose southern reaches were a stronghold of the radical anti-Western party Hezbollah. Syrian occupation of Lebanon had run deepest in the northern Bekaa, but now Lebanese soldiers controlled the checkpoints, waving amiably beneath murals of Kalashnikov-toting Shiite martyrs. Despite the Islamist atmosphere, the Bekaa is home to Lebanon’s excellent wine industry, and I had a quick snort in the tasting rooms at Château Kasara. A mixed group of Finnish, French, Irish, and Austrian tourists was over from Beirut, wandering the cool cellars and comparing notes. (Hints of sectarian feuding, with lingering aftertaste of summary execution.)

Slurring what little Arabic I could now speak, I negotiated a taxi fare to the Qadisha Gorge—UNESCO World Heritage Site, holy land of the Maronite Catholics, and heartland of Lebanon’s crazed Christian militias. The towns were festooned with huge posters of war criminals, but the gorge itself was Lord of the Rings territory: sheer cliffs decorated with waterfalls and vast Catholic cathedrals skewered in God beams of light. We finally topped out at the Cedars of Lebanon, one of five ski resorts in the country. Here was the last big stand—just a few acres—of old-growth cedars, some of them having lived 2,000 years. The dense canopy of evergreen branches created a green sky.

I should have quit right there, but instead I made an impulsive and foolish dash the next morning up Lebanon’s tallest peak, 10,131-foot Qurnat as Sawda, just behind the ski resort. Equipped with some croissants I’d stolen from the hotel breakfast, I hiked uphill for three hours, but was ultimately turned back by dense fog at about 9,000 feet. Using a compass, I navigated my way back to the top of the ski lift. It was off-season, but three construction workers built a trash fire to warm me up. “USA good!” they shouted. “Bush good!” They were Christians. Anyone who bombed Muslims was “OK!” with them. This included Israel (“Very good!”) and Ariel Sharon (“Number one!”). They danced around the fire, shouting out their idiot ski-bum agenda for the future. “Drinks good,” they screamed. “Girls good! Marijuana good! Bomb all Muslims!”

BACK IN DAMASCUS, the veneer didn’t seem ready to crack. At a glossy restaurant row full of the Syrian elite, men jockeyed BMWs and Porsches in the valet lots, and Syrian valley girls chatted on their cell phones and ordered sushi as tropical fish swam beneath their feet. Well-educated people told me that, honestly, no Syrians were fighting in Iraq. (Sixty-six have been captured on the battlefield.) No Syrians had been involved in the assassination in Lebanon. (According to Detlev Mehlis, at least six Syrian officials were aware in advance.) President Bashar al-Assad was a farsighted leader, a lovely man. If I knew him for two minutes I would love him. Israel was behind it all.

Meanwhile, the country held its breath. Outside the great Umayyad Mosque, black cars disgorged “regime elements”: colonels, generals, and secret policemen in tracksuits and dark glasses. Shiites and Sunnis pushed up against each other, crowded by Christians and Kurds. Even a congenital atheist could be swept up in the riptide of faith. On my last afternoon in Damascus, I followed a stream of Iraqi Shiite pilgrims through the streets of the Old City to the tomb of Raquaya, the daughter of Ali. Five hundred people were trying to enter, and 200 to leave, and the alley changed in an instant from absurdly crowded to dangerously panicked. Amid screaming, shoving, wailing, and angry chants, an elderly woman was knocked down and trampled under a sea of black chadors. Frightened children were passed over the heads of the crowd, surfing the high emotions of a Shiite Lollapalooza. We were on the verge of another ritual, the holy stampede. I fought my way out of the crowd with a new appreciation for the enormous, devotional suffering at the heart of Shiism.

Out in the vast eastern deserts, new defeats await. At the Roman ruins of Palmyra, a sleepy guard waved me into the Temple of Bel when I appeared at first light, too early for the posted hours. “OK,” he said wearily, “you can look.” A once prosperous stop on the Silk Road, Palmyra may possess the greatest array of antiquities in all of the Middle East, which is really saying something. Colonnaded avenues led for three miles through temples, courts, senates, and bathhouses, ending finally, fittingly, in mortuary towers that ran into the far desert. The futility of empire, the dusty brevity of human ambition, came crashing home, punctuated by the roar of Syrian MiGs passing overhead on their dawn patrol. Iraq was about 80 miles away. The Syrians are trying to close the border, putting up a berm to stop vehicles and pleading for night-vision equipment to track illegal crossings. But it is too late: America is already here. Army Rangers have already had bloody incidents of “friction” with Syrian patrols, and undercover commandos—”special-mission units,” in Pentagon parlance—have reportedly been sent in to stalk the safe houses of the Iraq insurgency. Like the past, the future is now.

Walking out of Palmyra at 7:15 in the sun-bright morning, I ran smack into the same Dutch tour group. Same minivan, same tour guide. “You see?” I told him. “The American is still alive.”

I left Palmyra in a powder-blue Mercedes with the voluptuous curves of the 1950s. For an hour we paralleled the invisible border, nothing but dust between here and the war. A traffic sign with a huge arrow pointed left: baghdad, it read. I went right.

As we raced for Damascus, straight as an arrow, a huge chocolate-brown hawk dropped into formation beside the car. The bird coasted above the roadside ditch at 60 miles an hour, barely moving a feather, grazing the top of the weeds, head down, hunting