Belize, Bonaire, and the Bahamas share more than a first letter—they are among the best places in the greater Caribbean to experience that increasingly imperiled wonder of the world, the tropical reef.

In the brine off Governor’s Harbour, Eleuthera. The Bahamas lie just beyond the Caribbean, in the Atlantic, but the warm shallow waters teem with marine life and also make an appearance in the series Saving the Ocean, which airs through January on PBS. View Slideshow

I made a sacrifice that night, an offering after my fourth day of being stranded in Punta Gorda, the southernmost town in Belize.

Offshore are the Sapodilla Cayes, a chain of fourteen barrier islands with some of the most pristine coral reefs in the Caribbean. I was supposed to be out there, participating in a science dive, dutifully collecting data on the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef.

But no. Wind covered the Caribbean in whitecaps, making the forty-mile crossing impossible. There was absolutely nothing to do, day after day—nothing but sit in bars while neatly coiffed Rastas mixed gin-’n’-juice cocktails. Nothing to do but walk around in stiff breezes, absorbing the quirky local culture: British diction, Mayan faces, Hindu shrines, Garifuna drummers pounding out the ancient rhythms of their slave ancestors. There was nothing to do but eat garlic shrimp and stay up late, staring gobsmacked at the things that go down on a Belizean dance floor.

And then on the fourth night, leaving the Reef Bar after a session of pretty much all of the above, I found that the bike I’d rented from my hotel wasn’t where I remembered leaving it. It wasn’t anywhere else either. In a melancholy mood, I walked a mile to the Blue Belize Guest House and stood in front, silently rehearsing my apologies.

That’s when I noticed: The wind wasn’t blowing anymore. The bike was a sacrifice to the wind god, and it must have worked.

Ha! I threw sixty dollars at the hotel desk, the replacement fee for the bike, and packed my bags right then and there. At dawn I almost ran that mile back into town and caught the first boat out to the Sapodillas.

I was heading underwater, here and around the Caribbean, with two questions in mind: What do we get from coral reefs, and what can we do to save them? Starting in the far west of our continent’s home sea, I would visit the Sapodillas and the Mesoamerican Reef, the second largest in the world, looking for the awesome biodiversity that peaks on healthy coral reefs. Moving east would take me to Bonaire, the arid diver’s mecca that shows every day what actually works in reef conservation. And with a final run to the Bahamas, I would triangulate our high hopes for the Caribbean and its adjacent shores in the face of both damage and resilience.

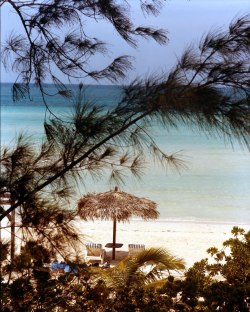

The view from Alabaster Bay, near Governor’s Harbour, is as stunning as its offshore life.

“Reefs are the canaries of the sea,” I was told by Don Stewart, who in 1979 co-founded the Caribbean’s first marine park, which protects the reefs of Bonaire. His equation was simple: “When the reefs die, the ocean is in big trouble.”

We’re in big trouble. Around the world, more than one billion humans, mostly poor coastal people, depend on the seas for the majority of their protein, and if predictions of reef collapse are accurate, 100 to 200 million of them could starve in the next two decades. Another 38 million who work in fisheries or rely on them will lose their livelihood. In addition to feeding us, reefs save lives and property by absorbing and deflecting storms—crucial as sea levels rise in the century ahead.

Oceans are hurting everywhere, but smaller sheltered seas like the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the Caribbean are the most threatened. The Caribbean—with the same population pressure as the Med but with warm water, making coral reefs so much more productive—is particularly vulnerable and may be the first to risk reef collapse. “Caribbean reefs were hit earliest and worst,” notes Carl Safina, a marine biologist and the presenter of Saving the Ocean, a ten-part PBS series that airs through January. Overfishing has depleted many of them, throwing off the self-correcting balance of predators and prey. Not only that, but the seas are rising and warming; during hot spells, corals are bleaching out, sometimes dying off en masse.

Safina can list threats to the Caribbean all day (“Wait,” he interrupted himself at one point, “I forgot about sewage!”), but he’s also the rare voice who talks about hope. Marine protected areas have an ability to help reefs recover; problems like overfishing and pollution are man-made and can be fixed as quickly as men care to. Many small Caribbean countries get fifteen percent of their GDP from reef-driven tourism, which creates strong incentives to protect the ocean, as do several potential cancer drugs that use components first isolated on reefs. Global warming is a long-term crisis, but slowly, plants and corals can adapt, Safina said, the marginal species moving in as today’s winners decline.

“We know how to deal with all of these problems,” Safina asserted. “The question is, will we decide to do so? Are we going to love the ocean enough to do something?”

A new Caribbean can emerge from the old.

Lip flare is not a Belizean dance move. It is the curling, outermost pink edge of the spiraling shell of adult conch. In Punta Gorda, I signed up to measure some of that lip, volunteering as a diver on a project in the Sapodilla Cayes that involved studying a colony of conch.

We need answers about reefs, but even rudimentary science can be difficult and dangerous underwater, requiring huge expenditures on research boats and thousands of dives to collect data. There is “too much ocean and too few scientists,” as Polly Wood, a founder of a Punta Gorda-based NGO called Reef Conservation International, put it. RCI matches enthusiastic amateur divers with marine biologists studying in the Sapodilla Cayes Reserve. Paying our own way to dive in Belize, we would effectively extend the reach of researchers by collecting data at remote sites.

PHOTOS

Beautiful Bonaire, Belize, and Bahamas

Rob Howard captures the beauty of these three islands in this gallery of photos and digital extras.

Bathing suit? Check.

Our payoff for this selfless labor was increased access to the reefs and islands of the Sapodillas.

We shot over a shallow green bay in a long panga, slowing only to watch a pod of shy dolphins, and then crossed onto a narrow band of deep-blue water. Aylen Usman, a Vancouver ecologist who served as dive master on the trip, had been watching the water and shouted over the roar of the engine: “I saw a shark almost every day last year. This year I haven’t seen one.” Fisherman—maybe Belizean, maybe Honduran—have been illegally killing sharks for their fins, sought after in China. Worldwide, about a hundred million sharks are killed annually for the Chinese market.

In the Caribbean, reef sharks are normally abundant as far north as Key West. Apex predators, they are killing a large part of the biomass on a healthy reef. Killing sharks throws reefs badly out of balance: Mid-size predators come to dominate, wiping out the small reef cleaners—the sea urchins and herbivorous fish. But “there’s real money in it, pound for pound as much as drugs,” Usman noted. Belize has acted steadily on marine conservation, expanding its sanctuary system in 2009, and I did see boats from the Belizean coast guard and fishery service patrolling the Sapodillas. Even so, the shark crisis proves how vulnerable the Caribbean is to the wrong kind—the criminal kind—of economic exploitation.

We powered over flat water, through the Snake Cayes, and almost forty miles out came to Hunting Caye, the tail of Mesoamerican Reef, 585 miles of coral heads that run all the way down from Playa del Carmen, Mexico. Hunting is a perfect sliver of sand a thousand yards long, one of Belize’s two-hundred some fringing-reef islands. Swaying palms, gentle waves, and a sense of natural isolation compensated for the lodgings: spartan dormitory rooms belonging to the University of Belize. The only regular visitors are scientists and their students, and volunteer divers like us.

That first afternoon, Usman took us straight out to our work site, called the Stadium. The pit in my stomach reminded me why I was here: The Stadium is more than a hundred feet straight down, a dark, ear-busting, head-crushing depth. To avoid decompression sickness—the bends—a diver could stay down there for just fourteen minutes. That’s why volunteers were needed: We were cannon fodder, racking up the minutes of data collection that no one scientist could. The ascent, filled with floating pauses to let the nitrogen creep back out of our capillaries, would take about three times as long as the descent.

We fell backward out of our boat and dropped slowly down a transparent water column, deeper and deeper. I cleared my ears seven or eight times; was the dizziness I felt from that fall, or from the onset of “narc,” the dangerous, dreamy state that hits some divers at this depth? We settled onto the sandy floor, a broad bowl encircled with coral sloping up and out at forty-five degrees.

The sand contained our quarry: queen conch.

These large shells normally flourish in shallows of thirty feet or less, easily reached by skin divers. Conch meat is delicious; they have been fished out of parts of Belize and much of the Caribbean. But here was a resilient surprise: The Stadium held a population of queen conch that was reproducing at a hundred feet deep.

The coral scientist Jeremy Jackson has popularized a graph showing the decline of Caribbean reefs; live coral now covers less than half the area it did in the 1970s, and the bitter argument among scientists is not over whether Caribbean reefs will collapse but when. Do we have just a few decades left, or perhaps a century? Jackson’s ominous arrow points to a post-coral Caribbean, a green bathtub where the featureless bottom is a deep slime of algae.

But straight-line predictions can’t account for places like the Stadium—the dark depths, the unmapped, uncounted, and unknown life. Most of the Mesoamerican Reef has never been surveyed for marine life. Scores of islands across the Bahamas receive not a single human visitor in a year. Cuba has more than a third of all Caribbean reefs, most of them never glimpsed by science. Maybe I was narced up, but at depth in Belize, it felt like the wrong time to declare reefs over; it is time, as Safina put it, to “get out there and try your best.”

Ticktock. I had fourteen minutes to add some numbers to the future. Usman handed me calipers, a tape measure, and a butter knife, the latter for scraping off the I.D. tags fixed to some conch by previous diver-researchers. I measured; my dive partner, a trainee dive master from England named Hannah, recorded the results on a white slate with a number two pencil. Clumsy, novice, and disoriented, I had measured the length and lip flare of just three conchs when there was a tap on my shoulder. Usman showed me the huge timer on her wrist: thirteen.

I put my tools in my pockets and followed Hannah as she swam over the sand and then up the gently sloping mountain of coral in front of us. I could feel the pressure subsiding—ninety feet, then seventy, sixty, forty—until we came to the top of the reef, at about thirty-five feet. There were green needlefish hovering here, a blue-tinged Caribbean spiny lobster jammed into a crevice, and waves of lettuce coral and gorgonian fans. A four-foot barracuda paid no attention to us, which is what you want from a barracuda.

Here it was: the best reef I’ve ever seen in the Caribbean. Decompressing in a motionless float, I shared the current with bright, tiny fairy basslets and a pair of gray angelfish that moved in devoted tandem. The reef was a vibrant collage of soft and hard coral thick with fish. Long barrel sponges gave shelter to a balloonfish, a school of mackerel whipped by, there was a black grouper, and an eagle ray fanned past on its way to the shallows.

Four of us were drifting, blissed out at the end of a deep dive. But I was the only one looking when a hawksbill turtle drifted up.

He was probably 150 pounds, with a carapace like Japanese armor and the leathery neck of an old man. Finning slowly, he looked at me from a dozen yards, evidently curious. Sea turtles are basically dinosaurs—unchanged over a hundred million years. Nothing in that long time span has challenged their survival, or that of the Caribbean, as the threats to coral reefs do today. Yet before action, there must be hope. Hope—for me, an ancient creature rising up in confidence, a survivor emerging from a world that defies belief—is the very first thing. Without that vision of a Caribbean still worth loving, can we really go forward?

If you need a reminder of what the future should look like, come to Bonaire. The national marine park created in 1979 was comprehensive, setting aside thousands of acres of reef to a depth of two hundred feet as a protected zone. And the park came about only after fifteen years or so of coral conservation efforts that pioneered no-take rules for fishermen and divers and bans on spearfishing and dropping and dragging anchors. Today, Bonaire’s corals are largely intact and are the basis of the island’s tourism industry. In survey after survey, divers rate Bonaire the Caribbean’s top dive destination of those reefs. Although some of these “best practices” have spread on a wind of grant money to destinations like the U.S. Virgin Islands and tiny St. Eustatius, coordination has been as scattered as the islands themselves. The United States alone has more than 140 laws governing ocean issues, administered by eighteen federal agencies competing for the same small budgets. No one is in charge.

Except you. Safina had urged me not to forget that tourism is a net gain for the Caribbean reef, what its downsides. “In cash-strapped places,” he said, “tourism provides a value to keeping things alive, and a strong rationale to protect things.” Once a poor and ignored outpost, Bonaire had acted early to draw in diving tourism; now it is prosperous, with what Safina called “the best remaining reefs in the Caribbean, with the possible exception of Cuba.”

Most diving here is done not with a boat but with a pickup truck. I rented one at the airport (DIVER’S PARADISE, the license plate read), loaded it with rented tanks and gear, and roamed the coast, picking from sixty dive sites within a forty-five minute drive of Kralendijk, the main town. The island was all arid sunlight and craggy, vertical shoreline, even underwater. I learned to pull over on impulse at whimsically named dive sites—rocky La Dania’s Leap, meditatively easy Front Porch, and azure blue Karapata—and team up with strangers. Even in our heavy gear, we could step through surf or off a boulder and be over coral in seconds.

Bonaire has wall reefs right in the sides of the island that burst with kaleidoscopic color. Angelfish dodged en masse, a red snapper scooted under me at one point. I saw a foot-long dogfish resting on the sand, cuddly as a basset puppy. There were soft corals waving like grass, car-size roundels of brain coral, and amphorae-like barrel sponges. The shoreline is so steep that while sitting in my truck, eating a sandwich after a dive, I noticed a sea turtle swimming under the window. Emily Dickinson was wrong to define hope as “the thing with feathers.” It has fins and a leathery old face.

Off Klein Bonaire, a small island in the harbor, I found some of the last large fields of staghorn and elkhorn coral you will see in the Caribbean. In the 1970s, disease wiped out these spectacular creatures from many other islands, but Bonaire’s coral, guarded by no-take, no-touch, no-anchor rules, fared better. In 2005 and 2006, radically warm waters across the Caribbean caused incidents of coral bleaching: When under stress, corals’ tiny host animals expel the symbiotic organisms that give them color, nutrients, and even oxygen. But the resulting white, deadened coral can recover; in Bonaire, the recovery rate was nearly 100 percent.

Those animals—small creatures called polyps—are the great builders of reefs, living in complex symbiosis with tiny plants and other animals. Secreting calcium carbonate to build millimeter-size houses, the polyps gradually add up, millions of them climbing upward and outward until they become the largest structures on earth. The process can be achingly slow—some species might take a thousand years to grow a reef fifteen feet. Reefs can (and have) endured for millions of years, occupying a lucrative niche, the transition zone where deep, cold waters—the nutrient-rich kind—are forced up to meet sun-powered shallows.

But “a coral reef is not just coral,” I was told by Sylvia Earle, the noted marine biologist. She compared the complexity of life on a coral reef to that great natural phenomenon, New York City. “A city needs taxi drivers, garbage collectors, teachers, and grocery store clerks,” not just buildings, she noted. On a reef, that tightly woven carpet of plant and animal life “makes the system function,” but complexity is also a vulnerability. Earle warned that reefs in the Caribbean are beginning to “unravel.”

Global warming is a threat deeper than just a temperature shift. A warming sea turns more acidic, and declining pH has already made it harder for coral polyps, oysters, plankton, and even salmon to form their shells and bones. An average of various studies suggests that acid will double in the oceans by the end of this century; acidification will damage reefs most where they are already weakened, whether by fertilizer runoff (the Gulf Coast) or boat traffic (the Florida Keys). Some places suffer from too much poverty (in Haiti I’ve seen trash slicks running ten miles out to sea), others from too much popularity (RCI’s Polly Wood once counted ninety-three dive boats on the horizon of northern Belize).

Bonaire got the mix right—popularity born of protection. Even the “house reef” about a hundred feet from the bar of my hotel, Captain Don’s Habitat, was a lively place (the reef, I mean). With a chorus line of divers watching from bar stools, I dove there once and found a spotted moray eel—teeth glittering with ambition, as if asking, where’s my blue party drink?

One afternoon I went up into Bonaire’s dry interior to interview Don Stewart, who founded that hotel and was the inspiration behind the original marine park on the island. Stewart arrived on Bonaire in 1962, and he pioneered the diving and the hotel business here; he has spent the decades since conserving coral reefs and fighting tourism-industry and political interests that resisted change. In the 1960s, acting without the slightest authority, he banned spearfishing, even taking one violator to the airport and deporting him.

In an evening of tall tales and boasts (“We went through a case of tequila a week!”), he denounced Bonaire’s current government for planning thousands of new hotel rooms but no water treatment plant. The island relies on traditional septic systems, which leach sulfate and phosphate into groundwater and eventually the sea, encouraging a bloom of algae. Flushing your toilet, Stewart said, smothers the reefs offshore. He’d paid for his own water treatment system at Captain Don’s Habitat; when that failed, he installed another one. Bonaire would kill itself, he warned, if nobody planned ahead. “Ask your hotel,” he called out to me, as I backed away from his house in the pickup truck late that night. “Ask ’em where your poop goes!”

When I reached Carl Safina, the marine biologist, he was on Eleuthera, a narrow island of sand in the Bahamas that is the easternmost edge of the Caribbean, facing the cold Atlantic. The eastern Caribbean, even the eastern side of many islands in it, is a rougher world than the west—colder and more exposed. There are six hundred to seven hundred fish species in the western Caribbean; by the Bahamas that number drops to about four hundred eighty. But Safina was out there to hunt the recently arrived lionfish, an invasive species that is doing tremendous damage to the reefs.

I also went to Eleuthera to track an invasive species: the human. On the twenty-five-minute hop from Nassau, with my wife and son on board, we flew over cruise ships the size of hotels and hotels the size of pyramids. The Bahamas gets more than 4.6 million visitors a year, eighty-five percent of them American. Is it really possible to have this scale of tourism—all the fun stuff from beachfront hotels to fish fries—and also have coral reefs?

The out-island atmosphere kicked in immediately on landing in Eleuthera: I rented a car with a personal check and a handshake, and we drove down the island’s spine for ninety minutes to sleepy Governor’s Harbour. Here, we rented a bungalow on a crescent of fine sand fronting the Atlantic. At dawn, crashing surf woke us up. After breakfast, I was in the calm water on the western shore with my toddler. After lunch came a nap. After the clouds turned pink—6 P.M., if not earlier—it was time for a mango daiquiri.

Where were the crowds? I’d recently flown the length of the Bahamas in a small plane, empty islands unfurling beneath us the whole way. The crowds concentrate in a few places; even on Eleuthera, most visitors are content to remain on rocky Harbour Island, the northernmost town, with its graceful pastel houses, hip hotels, and legendary beaches of fluffy light-pink sand.

Governor’s Harbour, in the middle of the island, was vacation quiet: There were more owners than renters, often the same families returning across decades. Down the beach, someone had started a hotel project—denuding a point with a bulldozer, digging a foundation—and then gone bust. Some of the construction debris would have settled onto neighboring reefs; the site was now an untended laceration that had leached so much silt into the ocean you could see the plume in satellite photos. Out here I met Ben, a cabinetmaker from Maine who has been coming to the same house on Eleuthera for fifteen years. He often went snorkeling on the reefs, and offered to take me with him for a closer look at the coral.

To my surprise, he showed up the next morning with a speargun. It was a low-tech device, a simple rubber sling firing an aluminum arrow without feathers. Ben was a lover of reefs but also a hunter hoping to put a lobster on the table. We would be free diving, the latest name for what used to be called skin diving: Hold your breath and head down deep. On the windward side we strapped on fins and masks, walked backward into the sea, and flopped into water that felt as buoyant and clean as liquid air.

We snorkeled out toward the reef, passing over a few tattered beds of turtle grass and sections of the island’s fringing reef. The coral looked dead, but I recalled Carl Safina’s pointing out that tougher, surf-line corals might move into niches left by species battered by global warming—one way the Caribbean could adapt to change.

About two hundred feet out, we came to the reef crest, named for the way it climbs toward the surface from depths of twenty or thirty feet. Though broken in places, the reef still wrapped Eleuthera with storm protection. The coral had grown in “spur and groove” formation, alternating walls that split up wave energy with chutes that discharged sand and debris.

The techniques of free diving are as old as the sea. You rest on the surface to lower your heart rate, then make an energy-efficient “duck dive” and start finning your way into the depths. One breath is one dive. Nervous and rushed, my first dives on the cresting reef were feeble bobs, just twenty seconds at ten or so feet. Some fish swam around, but the coral seemed almost lifeless.

On the surface, Ben told me to go a bit deeper, actually beneath the coral. Floating above, I watched him slip under like an otter, the speargun leading the way down. He went to twenty-five feet, probing into crevices and lingering upside down, sticking his head into the shadows. Jealous, I powered down and found that the reef did look very different up close. A bounty of mollusks was sheltered under every knob, and clouds of small fish were tucked inside the crenellations, invisible to the snorkeler above.

Ben found no lobsters. He’d caught many here over the years, but maybe that was the problem. The accessible Bahamian reefs have been stripped by our appetite for big fish and lobster, and now people routinely use boats to fish the outer reef, which displaces the problem.

But he floated up from one dive, chasing his bubbles, to report that he’d found a lionfish. I immediately made it down twenty feet and peered under the portobello-shaped knob of coral Ben had pointed to. In the dark, there was indeed an upside-down (to me) lionfish. It was painted in lush red, brown, and white stripes, with long spines trailing gossamer filaments.

Native to the west Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea, lionfish are fast breeders and have almost instantly come to surpass all other threats to Caribbean reefs. They arrived in the ’90s—probably released from an aquarium tank—and by 2007 had blanketed much of the Caribbean. They vacuum reefs clean of almost anything that moves, eating crabs, shrimp, and forty types of fish, especially the gentle herbivores that function as reef cleaners. With the big predators—sharks and large groupers—fished out, there is nothing left that can take on those envenomed spines.

Nothing but us, that is. The Bahamas, which has one of the worst infestations, has turned to the same appetites that fished out the reefs, urging spearfishermen to kill lionfish on sight, teaching people how to de-spine them, and searching for commercial markets for the fish. Indeed, when I interviewed Carl Safina, he was heading to a lionfish derby, with cash prizes and a fish fry (of you know what) to follow. Like me, like Ben, Safina is a dedicated fisherman; it is part of our love for the ocean. Now our appetites, our spears and hooks, have to become part of the solution.

The anxieties of free diving, the struggles, always vanish after an animal encounter. I followed Ben easily on the last and deepest swims of the day. For the first time in my life, I finned down and actually passed right through a reef, swimming through a dark crevasse, under an arch, and out the other side. I was desperate for air by the time I got up, but I brought something up with me that cannot be gotten any other way.

In the dark, truly inside this otherworld, I saw the future. Many reefs are hollow in places, opened by tide and sand, carved with tunnels and shelters. This one, which had seemed so barren from the outside, was actually teeming. There were the seeds of a better reef: thousands of juvenile fish, black and yellow and electric blue, probably baby butterfly fish and common chromis and ugly little goatfish. An intruder, I had passed through too briefly to note much. But there was one thing I definitely saw down there, lurking in the shadows: hope.

It’s not over yet.

Blue Beauty – Patrick Symmes – Byliner.

Originally published in Condé Nast Traveler, December 2012